Be Evil

A serious post about the fight for the future of the internet and a functioning society. Plus: a potato that can shoot a rocket launcher??

Last week Google and Meta, formerly Facebook, announced they would block access to all Canadian news content. They did this because Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government passed a bill, C-18, that would compel the tech giants to negotiate compensation for news outlets.

The companies had initially inked deals with several Canadian news publishers but are now tearing those up. Google, which once boasted the slogan “don’t be evil,” has decided it would rather hasten the death of Canadian news rather than share a pittance of its revenue. Meta, as an extra insult, even tore up a $4 million fellowship program to hire new reporters to the Canadian Press.

The fight with Canada is one flashpoint in a global story about how governments are dealing with a tech duopoly that has gutted local news across the world. The hardball tactics are really not about the costs of C-18, but scaring off other countries from passing their own laws to help their own news outlets.

If the Twitter discourse is any sign, many Canadians do not conceptually understand the point of the legislation. Much of the debate has been about how the bill institutes a “link tax.” Op-eds argue it is crazy to force Google and Facebook (Meta is a terrible name, I’m just going to call them Facebook) to pay when news is shared on their platforms. Social media is sending eyeballs to news sites, the argument goes. Why should Google and Facebook be charged for providing this favor?

In fairness, the legislation is unintuitive if you haven’t paid attention to how the internet evolved over the last decade and a half, and most people haven’t. Unlike the old go-to media doomer analyses like “Craigslist killed classifieds,” the problems with the modern internet have developed underneath the surface.

How Things Work

This is what happens in 2023 when you open a webpage1 and see an ad. First you are identified based on your past purchases, interests, and behaviors, which are constantly being tracked online. The website then pings an ad marketplace saying “this mid-30s woman interested in skiing, pottery, and collecting vintage pornography is visiting our website, how much will you pay us to show her your ad?” There is an auction and the winning advertiser sends their ad over to be displayed. This all happens in a fraction of a second, less time than it takes to load the page.

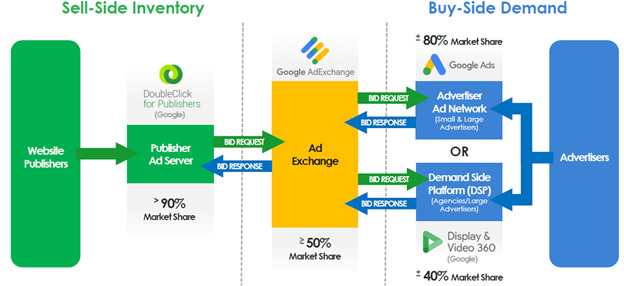

Here is the thing. The website uses an ad server, which is owned by Google. The ad marketplace is also owned by Google. Advertisers interface with the market via an ad buying tool, which is owned by Google. It’s like buying a house2 but you can only go through one agent, who also represents the seller and owns the listing software. Is that transaction going to be designed to give you the best deal, or to make the agent the most money?

Here’s an illustration of how it works from the US Department of Justice:

The reason there is this handy visualization from the DOJ is that they are suing Google over allegations that it used “a pervasive and systemic pattern of misconduct” to create a monopoly that has driven up costs on both publishers and advertisers, all the while using its size to crush competition.

The European Union is also accusing Google of being an illegal monopoly that needs to be broken up. This isn’t just some liberal crusade; in the United States a group of Republican-run states led by Texas were the first to sue Google over these allegations.

If you don’t care how adtech works or how we got here, you can stop reading after this graf. This is the answer to the question “why should we force Google to pay for news?” It’s not about Google sending traffic to publishers. It’s that Google bought up the guts of the internet and now uses anticompetitive tactics force itself as the middleman between publishers and advertisers, siphoning money from both sides through its monopolistic fees. The DOJ estimates that for every ad dollar spent that flows through its services, Google takes about one third, adding “for some transactions and for certain publishers and advertisers, it takes far more.”

As the Texas lawsuit puts it:

“Google started requiring publishers to license Google’s ad server and to transact through Google’s exchange in order to do business with the one million plus advertisers who used Google as their middleman for buying inventory. So Google was able to demand that it represent the buy-side, where it extracted one fee, as well as the sell-side, where it extracted a second fee, and it was also able to force transactions to clear in its exchange, where it extracted a third, even larger, fee.”

The Last 15 Years In Two Minutes

Up through the 2000s it was pretty viable to make money selling online ads around your content. As a result, we saw an explosion of websites and new media outlets. The internet was thriving. But in 2008 Google spent $3 billion to acquire DoubleClick, which had become the dominant online advertising company after a decade of its own mergers and consolidations. The pieces were coming together. Google had the most popular search engine to track online behavior, the tools to track that behavior, and the marketplace to sell ads customized by spying on users. Google’s business wasn’t just search ads anymore, it was all ads.

[This post won’t get into privacy issues, a whole other can of worms. But let’s just note that a huge part of the story of what drove Google and Facebook to market dominance was their unrivaled ability to track - to spy on - the habits of their users. It’s why the notion of competing for eyeballs doesn’t hold. A big reason your local paper can’t compete with big tech to sell ads is your local paper knows a lot less about you.]

Over the next decade Google used strongarm tactics to entrench its market dominance. It’s a classic monopoly story. Everyone was using Google tools, which meant you had to connect them through more Google tools, which allowed Google to demand larger slice of the pie at each step.

Around 2017 publishers and rival tech companies fought back with something called header bidding. When an outlet placed ad space up for sale it would be routed through multiple ad exchanges, rather than just the one controlled by Google. Google had tried to ban this because, as publishers quickly found out, you could get better deals on rival exchanges that weren’t subject to Google’s extortionate fees.

Here was the fork-in-the-road moment for the internet. In 2017 Facebook, then known as Facebook, announced it would get into header bidding, meaning that Facebook advertisers could bypass Google altogether. A genuine threat to Google’s market dominance had emerged.

Instead, Google and Facebook cut a deal to become a cartel. Google created its own version of header bidding called Open Bidding and Facebook signed on. In exchange, Google gave Facebook - allegedly, according to the Texas lawsuit - a leg up in its auctions. Google and Facebook still theoretically compete for ad dollars, they just do it in a way that ensures they both come out on top. If you’ve seen Rounders, think about the scene where the poker sharks sit for hours at the casino draining tourists of their money. “We’re not playing together, but then again we’re not playing against each other either. It’s like the Nature Channel, you don’t see piranhas eating each other, do you?”

(Before you judge me for making a Rounders reference, know that Google internally named these plans and schemes after Star Wars references, “Jedi Blue” etc, which I’m sparing you from.)

Google managed to convince a federal judge last year to toss out the collusion with Facebook charge, but the rest of the Texas lawsuit is going ahead.

This gets us to where we are today. Two companies make half of all online ad revenue while newspapers close en masse and all news outlets face round after round of layoffs. In Canada in just the past week one of the major networks, CTV, announced it will try to abandon local news altogether while the largest paper in the country, the Toronto Star, announced plans to merge with the last major newspaper chain, Postmedia, which is owned by an American hedge fund sucking it dry.

It’s not just legacy media suffering. Online outlets founded in the digital age are going through wave after wave of layoffs. Vice is in bankruptcy. BuzzFeed bought Complex and HuffPost in a bid for size but it hasn’t worked. It just shuttered BuzzFeed News, where I used to work. And of course local news in particular is dying, bringing all kinds of frightening prospects for maintaining a fair and enlightened society.

Stopping the Plunder Down Under

Australia looked at this state of affairs and decided to do something. They couldn’t fix the internet on their own but they could demand that, at least in Australia, the tech duopoly had to share some of its profits with the local news outlets they had been bleeding dry. They passed a bill locking platforms and publishers into a kind of binding arbitration over how much.

The duopoly tried to bully them out of it. Facebook shut down access to all Australian news sites, including hospitals, emergency services, and charities. The company claimed those moves were accidental, but whistleblowers told The Wall Street Journal it was a deliberate strategy to pressure the Australian parliament to abandon the law.

The blackmail didn’t work, the legislation did. People were outraged by Facebook’s callous moves. Both it and Google caved and struck deals with news sites.3 Those deals injected cash into Australian news which, according to one analysis, led to a spur of hiring local reporters:

Bill Grueskin, a professor at Columbia Journalism School who authored the report, said that the Google and Facebook payments were used to create at least 50 new journalist roles in underserved parts of the market.

He said that Monica Attard, a Sydney-based media professor, had described the market for entry-level journalist roles as being the best she had seen in 20 years.

The Future of the Internet

There’s a view in Canada that the government is forcing tech companies to pay for news just because it doesn’t like how unfathomably wealthy they are. There’s a view that the Google/Facebook moves are a logical reaction to legislation so we shouldn’t have pushed them to begin with.

This misses the key point that the state of affairs with Google and Facebook is not just a cryin’ shame, it’s that it is an illegal antitrust violation. The bedrock of antitrust is that you’re supposed to compete and innovate your way to success, not use a dominant market position to crush competition. Even setting aside the allegations of widespread flat-out fraud, if the tech duopoly rests on anticompetitive behavior then countries are obligated to take action to protect consumers and competitors from harm.

What Australia and now Canada are doing is, admittedly, an ad hoc move to address an antitrust problem. The normal way to deal with a monopoly is to break it up,4 and that is what the US and EU are looking to do. But that may take years. In the meantime the Australia model does something to rebalance the scales of a broken ad market, to give news a lifeline. C-18 is projected to be worth $330 million per year for Canadian media.

Perhaps the biggest potential downside is that Google and Facebook try to reduce traffic to news sites to keep costs low. Google and Facebook have already shown a brazen disregard for the health of Canadian society and there’s no way to know how long they’ll hold out. In the meantime, new outlets suffer. Many pundits have justified this lowering a death knell to news sites, and blame Trudeau for trying to change the status quo to begin with. He leads a shaky minority government and it’s not hard to imagine that he folds.

But this is a global fight, not just a Canadian one, and clearly there is a growing appetite to crack down on this duopoly. Forcing them to divest their adtech stack, payments to publishers, privacy laws so that the internet once again becomes about winning over viewers not being better at spying on them, it’s all on the table now.

That’s why Canada could win this staredown. Google and Facebook risk other countries looking at what’s happening in Canada and deciding maybe these two companies should not have the power to hold a gun to the head of any country who dares to challenge them.

Now For Something Completely Different

One quick recommendation before I go. A few months ago Bloomberg’s Jason Schreier laid out a theory on the Triple Click podcast that all videogames can be classified as “flow games” or “thought games” (or some combination of these two types.) For a flow game think about fluidly cruising through a Mario level or playing a reflexive, quick-twitch round of Call of Duty. Thought games involve sitting back and making tactical choices, as in playing a strategy RPG.

I don’t know if there’s any more jarring a merger of these two than Brotato, an indie game that launched it’s version 1.0 last week where you play as a six-armed potato wielding a variety of weapons to fight off alien invaders. The actual gameplay is almost insultingly minimalist - you move around a map dodging enemies and picking up loot. The aiming, shooting, and looting is done automatically. You do not need to press a single button.

And yet

And yet Brotato is one of the most addictive thinking games I’ve tried in a while. In between levels you go to a shop where you have a deep pool of tactical choices to make about what weapons you use, what items you supplement them with, and what stats you upgrade. These choices, not your joystick prowess, determine victory or failure. The whiplash between flow state and think state couldn’t be more stark, and it works.

If this sounds like last year’s breakout hit Vampire Survivors, it is. But I got bored pretty quick with Vampire Survivors and in my limited time playing Brotato I’ve found its choices - which frequently involve hurting yourself in one category to get stronger in another - to be more interesting and satisfying. Plus it only costs four dollars. To get a sense of how to play you can watch this primer video from streamer Jorbs. Or just do what I did: jump in and get killed over and over, while still having fun.

Things work a bit differently in apps but it’s similar. There, again, Google has software for every leg of in-app ad buying. In some ways the apps are worst because there big tech also takes a big cut of subscription revenues intended for a news outlet.

Look, you try coming up with a snappy metaphor for how this stuff works. Texas attorney general Ken Paxton went with baseball, which I think makes less sense but it’s a good quote. “Google is essentially trading on ‘insider information’ by acting as the pitcher, catcher, batter and umpire, all at the same time. This isn’t the ‘free market’ at work here. This is anti-market and illegal” he said.

Opponents of the Canadian bill were quick to point out that much of the money went to Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp. And it did, because News Corp owns a big share of Australian news. It’s not ideal but this is a bit of a Catch-22, mate. People bemoan that as news becomes less profitable it is increasingly concentrated in the ownership of a few big companies, then object to making news more profitable because the big companies will benefit.

Many have argued Canada should set up some kind of tax credit or journalism fund to help outlets instead of making Google and Facebook pay. I disagree. When you’ve got a monopoly problem the solution is not to keep the problem in place and have the public subsidize the parties being victimized.