How To Resurrect A Lost 31-Year-Old Board Game Into One of The Best Games of 2023

A conversation with the publisher of Zoo Vadis about how to create a modern classic out of conniving crocodiles and backstabbing marmosets.

A common progression for board game players in their 30s goes like this: you grew up playing the same staples as your parents like Risk, Clue and Monopoly, in the 2000s you got really into Settlers of Catan, you played Catan until you got tired of it and then you branched off into other games like Bohnanza or Ticket to Ride or Carcassonne or Seven Wonders or Pandemic. Now there’s a new board game for every theme you can think of, from dystopian Eastern-European steampunk to cheesemaking.

In recent months I’ve become less interested in trying to keep tabs on hyped new games and more interested in catching up on lost classics released before the modern explosion in tabletop gaming. I can’t say I recommend it. Some do get dusted off for a modern reprint (the recent 25th Century release of the exquisite 1999 auction game Ra is about as good as it gets), but others are long out of print and expensive to come by.

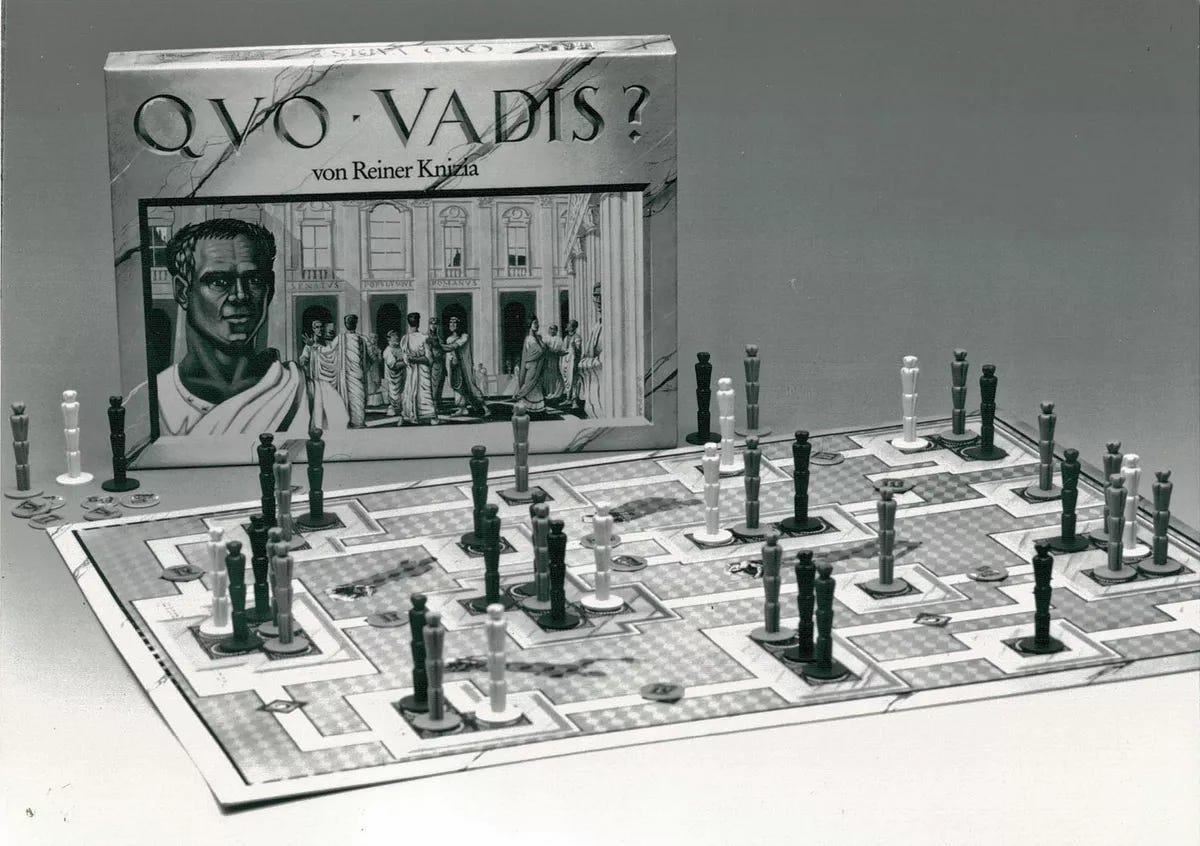

Zoo Vadis, a three-to-seven player negotiating game by Reiner Knizia and so far my favorite board game of the year, is something a bit different. It’s an Evil Dead II of a game, serving as both a remake of the 31-year-old Quo Vadis, which I’d never even heard of, and also a sequel with some genuinely groundbreaking new ideas. Quo Vadis was a negotiation game where Roman politicians tried to politick their way into the Senate. The gameplay was supposed to be great but it was mostly lost to time, probably because it presented like this:

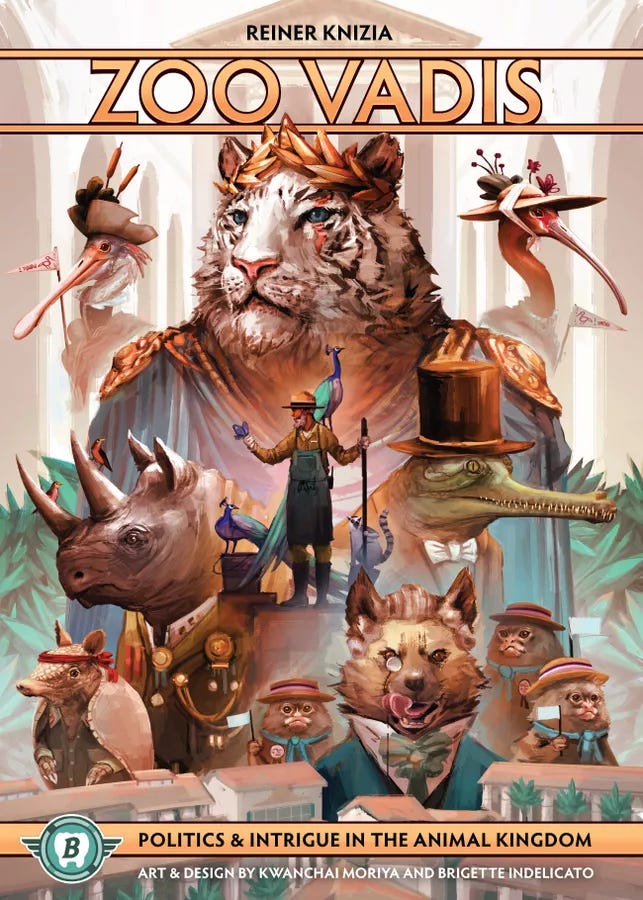

Not exactly a looker. Bitewing Games, a small publisher founded by two dentists, revived and remade the core game with a new theme and some new rules. They went with a slightly more dynamic art direction:

Look at that smoldering tiger. Tell me you don’t want to see what’s inside this box. Ok so they swapped roman patricians for anthropomorphic animals trying to gain supremacy of a zoo. That’s cute, but what’s interesting is that they looked through three decades of player reviews to see what people liked and disliked, then used that feedback to reshape the game. The result is something deeper and more satisfying. In this post I talk to Nick Murray of Bitewing Games about how to modernize a lost classic. But first, the game itself:

Zoo Vadis Review - How it works

The central tension at the heart of Zoo Vadis is it is both a race and a competition to get rich. Players take on the role of intelligent zoo animals moving from pen to pen, negotiating their way up towards the very top of the board, the star exhibit. There are only a handful of slots in the star exhibit and once they’re full the game ends immediately. If one of your animals isn’t inside you cannot win the game.

To advance you need a majority vote of animals in a pen1 to vote you forward. If you have two hyenas and the third slot is held by a rhinoceros, no problem, you can vote yourself forward without any help. But usually you will not have a majority and you will need to woo votes from opposing players. Those players will demand bribes. You can bribe them with laurels, the game’s version of money. And here is the catch: while you need to reach the star exhibit to be eligible to win the game, the actual winner is the player with the most laurels.

On one hand you need to swiftly get to the finish line. On the other, hanging back and extracting bribes like a manipulative tollkeeper is both lucrative and satisfying. Diverting from Quo Vadis, there are also non-playable peacocks that you can either bribe at a flat rate or move to somewhere convenient for you/inconvenient for your opponents. These peacocks, let me tell ya. At times you will love them and at times you will curse them. They can be exploited as a key step in a path to victory or thrown in your way as plan-ruining barrier, depending on how they are moved around the board.

Another big difference from Quo Vadis is each player has a special power unique to their species - move an extra space, move into a full pen, gain more laurels, etc. But, twist!, you cannot use your power on yourself. Instead you can only sell it to another player and hope to come out ahead on the deal.

Why it works

Zoo Vadis’s tight map becomes a cauldron of constant interaction. The only way to win at this game is to be regularly making bribes, taking bribes, and selling powers. What’s more fun than shaking down your friends and family? What’s more pure than working out a mutually beneficial deal with a dear, longtime friend who is visiting town that you haven’t seen in ages and then reneging on that deal and instead moving a peacock in their way?2

The game is quick to learn and plays in a breezy 30-40 minutes. It has the simple-rules-but-deep-strategy mix that the best games by designer Reiner Knizia are known for. Deliciously tricky situations are constantly arising. Players will start filling up the star exhibit with peacocks, causing the armadillos, who had thought there was plenty of time left, to break into a desperate sprint for the finish before the door slams shut. Logjams will be resolved because of clever trading of player powers. An marmoset and a hyena will get into a bidding war for the support of a crocodile.

Zoo Vadis feels like a mix of old and new. Its clean core ruleset plays like a decades-old classic free of the bloat of so many modern games. There are just enough options on a given turn to keep things interesting, but few enough to keep tensions high. The new theme, vibrant components, and characteristically modern spin of asymmetric player powers all fit in beautifully. That you cannot use your player powers on yourself feels like it will be an influential idea and one I’d love to see applied to future negotiation games.

A second opinion

For a goofier and decidedly more British take on the game, you can also watch this Shut Up & Sit Down review:

Let’s talk to the publisher

Nick Murray, one of the dental hygiene enthusiasts behind Bitewing, games had an in-depth post about the process of adapting Quo Vadis into a modern game. He looked through three decades of player reviews to find out what people liked and didn’t like. It turned out people loved the tense decision-making and engaging arc of play, but didn’t much like the look of the game or the limited player count (the game only clicked with four or five players.) One player lamented there not being more negotiating tools. He set out to fix all three issues.

Nick proposed adding neutral characters, which can be applied in different numbers to balance the board from three up to seven players. He also suggested adding asymmetric player powers for more depth. Original developer Reiner Knizia went to work implementing these but found the player powers backfired - giving people more creative moves made them less dependent and less likely to negotiate. Knizia had the breakthrough of players not being able to use the powers on themselves. As for the new theme, it was inspired by this plate Nick and his wife added to their wedding registry.

“I really wanted to squash the idea of this game looking dry or dull, and so the concept of spotlighting different animals on each of the screens (much like our dinner plates) with massive and vibrant art really appealed to me,” Nick told me.

He concedes that the anthropomorphic animal bit has been used a fair amount recently, but said the theme of players moving between different enclosures, or pens, was a natural fit with political animals campaigning their way through exhibits. Nick and I talked over email recently. Here’s our conversation, with my questions in bold.

First off, did you see the recent meme of women asking men how often they think of ancient Rome and being shocked at the frequency in their answers? Are you sure you shouldn't have stuck with the original theme? You could have been sitting on a gold mine.

Haha, my own wife actually asked me that question recently (it was the first time I had heard of the meme). I was surprised by the meme as well just because I feel like I never think about ancient Rome (outside of board games). Perhaps we did abandon a gold mine at the worst possible time, but then again we now have dapper marmosets and insurgent armadillos, and I wouldn’t trade them away for the world, haha. In all seriousness, we felt that gameplay of this design was elegant and approachable, so we wanted a theme and presentation with a wide appeal. We’ve already had players telling us that it has been much easier to convince their friends to play Zoo Vadis compared to the dry looking Quo Vadis, and that’s a win for everyone.

Ultimately we're playing these games with other people and you've talked about how hard it was to convince people to play Quo Vadis given its bland aesthetics. Clearly Bitewing put energy into making Zoo Vadis look more vibrant and inviting, which I would never say is a bad thing. But as the industry relies on crowdfunding campaigns I feel that I see a lot of games that highlight the miniatures and the theme of ancient gods or whatever, but the mechanics of the games themselves get short shrift. Do you worry that broadly we're too caught up on style over substance, or am I just getting caught up on some negative examples?

I do think there is a style over substance problem in the industry, especially with crowdfunding. For every creator with a genuinely great idea and the drive to share their vision with the world, there seems to be ten more projects that are gunning for a quick and easy cash grab either with a me-too knockoff design of a popular game or with a far too ambitious production packed with far too much plastic. On top of that, the barrier to entry is so low that you often see folks with creative minds yet very little development or business savvy jumping in and quickly finding themselves in over their heads with half-baked designs or with financial/logistical disasters. As a creator, it is so easy to fall in love with your baby and not see the flaws in it.

When a Kickstarter project fails to deliver on its promise (for any number of reasons), that hurts all Kickstarter creators. Folks become less willing to back games on Kickstarter once they’ve been burned one-too-many times. Fortunately, there are many battle-hardened backers out there who are able to recognize red flags in a campaign, dodge those pitfalls, and continue to support the more credible creators.

In the moment, it can be discouraging to see a project with all style and no substance receive far more support than a project that prioritizes substance above all else. As a publisher, we definitely feel a pressure to provide folks with solid reasons to back our projects rather than “wait for retail.” Unlike bigger companies, we do not have the funds to mass produce the game if we don’t have enough support for our Kickstarters. It’s a very hard balance to walk between exciting and incentivizing Kickstarter backers while sticking to what is ultimately best for the game experience and for the business.

But the thing to remember about projects and companies that put style above all else is that they are often gone in a flash. The games and companies that stand the test of time are the ones that prioritize substance and experience above all else. That’s what we’re trying to build, even if it’s a slower process.

I've never played Quo Vadis but I felt I could relate when you said some variants added in later versions annoyed you because they distracted from the core gameplay. It feels like in game design if you're not careful you can easily fall into the trap of adding more for the sake of more. When you're looking at adding a new element to a game how do you go about assessing whether it's improving the experience rather than muddying it?

For me personally, it helps to maintain a vision of the game’s strengths and weaknesses. If a new element dampens the game's biggest strengths, then it should be cut. If it shores up the game’s weaknesses, then it is probably a worthwhile change. I often like to do a SWOT Analysis (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) when evaluating our projects and games — a clean list of bullet points that paints a big picture of the game. This often makes certain ideas and their merits become obvious. Sometimes it is not so black and white, though… like a modular expansion that really clicks with some players and not with others. In those cases, you have to follow your gut.

You guys took the concept of asymmetric player powers, a staple of tabletop games, and flipped it on its head with the rule that a player cannot use their power on themself, and must instead sell it to a rival player. I think this is something of a stroke of genius and I've played some very fun rounds involving overzealous players aggressively hawking their abilities. Why did you conclude this new element was needed, and how much does it distinguish the play of Zoo Vadis from Quo Vadis?

There was one Quo Vadis player on Board Game Geek who commented that they wished there was a little bit more to negotiate with. In my research of Quo Vadis across the many forums, comments, and reviews, this was one of the comments that stuck out to me the most. It’s fun to exchange votes and laurels and promises of actions, but some part of me agreed that it would be cool to have just one more bargaining chip to work with. I think that comment combined with my recent plays of Sidereal Confluence (a very asymmetric, heavy negotiation game that I love) led me to the idea of introducing asymmetric abilities as another negotiation tool in Zoo Vadis. I suggested this idea to Reiner Knizia, and he was the one who settled on the requirement that you can never use your own abilities, you can basically only sell them.

Although you can only use your abilities on other players twice in a game (unless you earn a token that resets a used ability), I feel that this addition really blows open the doors of negotiation possibilities. Now you can insert yourself into a deal even if you aren’t present in the exhibit where the action is taking place. Now you have more ways to entice your opponents to help you out. Each animal ability essentially breaks a rule of the game in a really fun way, and they can be combined to allow for very powerful actions, so they almost feel like tools in a negotiation sandbox for the players to creatively conjure deals and arrangements. We’ve heard a lot of people say that they can’t imagine playing Zoo Vadis without them, which is a very nice compliment to Reiner’s ability to iterate on a core concept.

I feel like I'm going to be playing Zoo Vadis for a long time, in no small part because the core mechanics are so sound. And yet I think I'd never have heard of this game if you hadn't remade it. Are there any other pre-2000s hidden gems you'd recommend people seek out?

Oh boy, there are so many hidden gems out there! Just from Reiner Knizia alone there are dozens of overlooked jewels. That treasure hunt has honestly become part of our business model. Zoo Vadis is the first game in our new line called the “Crown Jewel Selection: classic gems, now polished and perfected.” We’ll be releasing a few more titles in this line over the next couple years, possibly longer, so keep an eye out.

As for pre-2000s recommendations, here are just a few that come to mind:

Bus is one of the first worker placement games ever made (way back in 1999) and from publisher Splotter Spellen (also now Capstone Games with a newer edition). This one is mean, cutthroat, and wacky, but it hasn’t aged a day. And it is Splotter’s most approachable game by far.

Condottiere is a clever card game featuring game-of-chicken auctions and tight area influence competition. I’ve had a lot of success showing friends and family this game.

Wildlife Safari (also known as Botswana) is a brilliantly simple little shared incentives card game by Reiner Knizia. There are many different versions now, but I picked up a delightful Japanese edition recently put out by publisher New Games Order. The more I play it, the more I love it. I’ll spare you my dozens of other hidden gem Knizia recommendations and simply suggest our video series currently going on the Bitewing Games Youtube Channel: the Ultimate Reiner Knizia Tier List where we rank and discuss over 150 Knizia games from roughly 1000 plays of research and exploration.

For those interested in a bit more detail: You actually need a majority of the total spaces in each pen, regardless of how many animals are currently in it. So if you’re the first to move into a pen with five spaces you’ve got to wait for at least two more animals to get there before you can reach the threshold of three votes needed to advance. This leads to some cool dynamics, like two players racing to stuff their own animals into a large space, or say Player A moving in a peacock for a crucial vote only for Player B to move the peacock further ahead, screwing over Player A’s plan and temporarily trapping them.

Mike, if you’re reading this, I regret nothing.